By Guillermo A. Muñoz Diego

In this essay I will discuss why a host government should have a licensing system[1]rather than production sharing contracts with IOC, under certain conditions and factors. The main arguments to be discussed include:

- The licensing system allows more flexibility to the IOC, in which the company will encounter a profit maximization problem with less restrictions.

- Licences in comparison with contracts do no not require high monitoring costs.

- Licenses can also incorporate certain limitations and conditions but ultimately the state holds de right to change the conditions of the license.

- For most developing economies, the oil and gas sector is seen as an area of opportunity to generate growth and revenues, thus I defend the argument that a Work Based Bidding could be a great alternative because it addresses the overall spending on the project.

- I will defend the threshold tax as one of the most reliable and efficient, because it considers the return to the investor when taxing and promotes consequent investments in the project.

[1]The offering of petroleum investment opportunities to private entities by a suitable tendering process and establishment of terms and conditions for award (Bunter 2002 cb Hunter).

I would counterargue that if the host government is a non-developed economy with no reliability, a production sharing contract could be the only way to ensure the IOC will take the risk of investing. This instrument provides them with more certainty that the license doesn’t. Nonetheless, at a high political risk, even PSAs could not be protected, like the case of Somalia in the early 2000s. For the previous arguments I have assumed that the countries are either developed economies or developing economies with some inefficient and struggles, but not with a high political risk. This would be the case of Indonesia, Mexico, Brazil, Nigeria, certainly not Libya, Somalia or Venezuela.

Even if licensing systems have been more common in developed economies like the US, Australia, Norway and the Netherlands. One of my approaches is that in developing economies with bureaucracy, regulation issues and inefficiency, a license system can mitigate better monitoring costs, bureaucracy costs and overregulation costs (agency costs essentially).

- In free market conditions, and according with the liberal theory, to leave the maximization problem with a few restrictions for the company will lead the company to maximize its revenues, and with an optimal tax rate, the government would receive the optimal share of the economic rents. With a PSA the company must comply to more terms and conditions that ultimately lead to higher economic constraints, the government could receive a high share of the profits, but this wouldn’t mean it is the optimal share of the profits. They could’ve received more, by allowing the company to incorporate more flexibility (real options financial theory) in their own capital budgeting model.

- For many countries, specially developing countries that may not have very efficient regulators, issuing licenses can help to reduce substantially agency costs. Even if it is the case that developed economies have used more this system rather than PSA’s (Al-Attar & Alomair, 2005), emerging countries like Brazil, Russia and Nigeria have still used them[1].

[1]They utilize a hybrid system of licencing, where both PSCs and concessions are used (Hunter 2015)

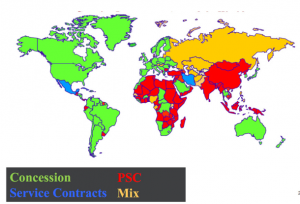

In the international scenario, it is somehow divided the countries that use licences and the ones that use PSC (2B1st Consulting, 2012). Now Indonesia has a mixed system, and Mexico has both PSC and licenses, to be updated from the map.

Some may argue than the lack of monitoring has caused also, disasters like the Macondo incident, but certainly, this could have been avoided by having to incorporate the willingness to pay and to accept if UK Health and Safety Code had been stricter. BP could’ve not tried to take high risks if they incorporate those potential liabilities to they capital budget. Even with PSA you may have asymmetries of information. The licenses include certain regulations they must follow, a relinquishment plan, local content provisions, a development plan, so the company is not entirely free of doing what they please.

If the regulators are not capable to monitor efficiently, they will do it at a high cost, these costs most be taken into consideration when the government has a share of the profits in a PSA. Technically they could be charging a higher share of the profits using a PSC but at the loss of significant monitoring expenses.

- Developing economies are always concerned that the large IOC will take their resources, by issuing licenses, the state can use this as a negotiating tool with countries to agree to better terms (Moss, 1998). Undoubtedly, this uncertainty may lead to disincentive investment but in the case of developed countries with a clear and solid legal framework the latter doesn’t seem to weigh greatly because at the end, it is a trustworthy country. In the case of the UK, when large blocks were left undeveloped by years, the UK Authority used this power to revoke the licenses from the companies (Kemp, 2019). It is not commonly used, but it could be a bargaining tool, surely.

- Regarding the way to assign a license, I believe the work-project bidding includes positive spill overs like job creation and additional benefits for suppliers and third parties (Hunter 2015). This way of awarding is consistent with the previous argument of maximizing revenues, because taxes and royalties must be paid even if investments costs are high, which could not be the case of a PSC based in profit.

A WPB takes into consideration an exploration/development plan, a proposed investment amount, which I believe is more useful for a government than just receive profit oil. Governments can have multiple intentions and would have to address different issues, but in the clear majority they would have a positive response from the public if they attract substantial investments that spillover into tax revenue, more jobs and higher commercial trade. Populist governments could be concerned with easy and fast revenue for the government, like the case of Venezuela. Parliamentary regimes which are more stable, tend to care more about the sub sequential investments, whereas Presidential regimes which last some years, seek early revenues for their public projects.

- The core section of the license is the definition of the royalty and tax. Addressing both the profitability of the company and the revenues for the government, it is important for the government that the companies are doing well, because to an extent that has a positive impact on government take (by maximizing the NPV of the licensed field/block the government receives a higher share as well). Under the resource rent tax, it is impossible for a project not to be profitable because tax is incurred once the costs have been recovered (plus a threshold, typically 15-25%). The down side is that there may not be early revenues for the government, but certainly if they have the license under a WPB, they must comply with the goals and objectives set there.

The threshold recovery is also a tool, that resembles a subsidy, for the government to grant investors more certainty on their investments, thus encouraging to reinvest during the project (Kemp, 2019). The early revenues for the government can be somehow mitigated by a non-abusive royalty (Hunter, 2015). The resource rent tax will address the economic rent properly, will not disrupt the investments, furthermore it will encourage companies to keep investing because it ensures them of a low payback period.

Under this scheme, all the costs are shared between the company and the government, except for exploration costs in the case of a dry hole, if resources are found, then yes, they are shared as well through the tax. The tax is progressive, the higher the profits are, the higher the share of the government, takes into consideration the oil price and it targets economic rents. In this sense, it doesn’t generate distortions (Kemp, 2006).

In the case of the royalty, it doesn’t target economic rents because it is centred in the revenues and not the profits, nonetheless a non-abusive royalty, combined with a reasonable threshold rate, can mitigate the distortion effect of the royalty (Sunley, et al., 2002). Positively, the royalty bidding system allows for companies (also small companies, because in comparison with cash bidding they don’t need the money up front) to bid in a higher competitive environment, theoretically leading to results closer to the efficiency level of bid; nevertheless, unexperienced companies, or too optimistic companies might bid to high in the royalty, and because it is not targeted in economic rents, a high royalty can generate serious problems and may result in abandonment (Kemp, 2006). This is certainly costlier to the state. The royalty can be based on a different number of factors: production, ad valorem (revenue) or an R-factor, that considers the ratio of revenue and costs, this last one is certainly the closer to target economic rents.

Ring fencing is also an important issue, by limiting the company to just one field, it can discourage exploration in other fields. Most of the companies will want to deduct all the costs with investments they have in the whole country, but for the government it could be more profitable to ring fence around a block, to encourage exploration and sequential investments in the same block (Kemp, 2006). In the case of the resource rent tax, companies may try to gold plate the costs under the license of the RRT to receive compensation for costs and investments that were incurred in another block, by ring fencing, the investment per km2 on that block can rise high enough to fully take advantage of the resources in the area.

We have not discussed relinquishment, it was a big issue in the UK that blocks where a license was given were not being developed. If the license system is based on letting the company solve their own profit maximization problem, they may realize that under the current market circumstances the best option is to delay development. Given that this is not the core of this essay, I will just argue that it is important for the host government to take into account relinquishment obligations in the work-project of the companies or in the license granted.

Naturally, my recommendation to a host government will vary from country to country; the government’s objectives also must be taken into account; ¿is it a mature province or they want to incentive exploration? All of the previous may affect on the judgment, in general, I am more in favour of low monitoring from the government, legal certainty and liability clauses, giving more freedom to the companies because this could guarantee more investments to arrive.

Government sometimes don’t consider all of the surrounding costs of preparing contracts, highly regulating, and monitoring, they could be receiving higher profits under a production sharing agreement, or by increasing monitoring but they don’t realize the spending needed for this. The license involves less spending from the government, it is in the larger extent, just receiving a rent from their resources. If they were highly efficient, I wouldn’t hesitate: production sharing contracts and receive a higher share.

It is true that the interests of the companies are not aligned with the ones of the government, a complete unregulated license will generate other market failures. It is not enough to argue like the Chicago School, that companies will maximize the net present value of the licenced field/block. Governments also take into account domestic supply, local content, balance of payments, the federal budget, in general, spillover effects (Kemp, 2019). That is the reason why I believe that the work-project bidding allows the government to look for the companies that are willing to satisfy more these government objectives.

A lot of factors must be well-thought-out, but governments must always have to respond to certain questions: 1) ¿does this measure generate any distortions? 2) ¿are we covered under high prices and low prices? 3) If we are to strict on companies, the current contracts may be to tough and lead to abandonment, and other companies may not invest, 4) ¿is this measure targeted on economic rents? 5) ¿under this measure, what are we incentivising? ¿exploration, more investment, gold-plating? (Kemp, 2006)

There are no one perfect way of awarding petroleum contracts/licenses in some countries ones have failed and others have succeeded, but having the insights previously mentioned can certainly make the awarding system more efficient, or at least, clearer for the host government.